By Peter C. Rowe, MD, Kevin R. Fontaine, PhD and Rick L. Violand, PT

In Part 1 of this two-part series, we outlined the series of observations of patients with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) that has helped us develop a new approach based on advances in neurophysiology and the fields of physical therapy and osteopathic medicine. In Part 2 below, we explain our current research to understand how manual therapy might complement other approaches to treating CFS, including managing orthostatic intolerance, to bridge the gap between the characteristic post-exertional worsening of symptoms and being able to better tolerate activity.

On the basis of the observations described in Part 1 of this article series, our current research has focused on the prevalence of areas of adverse neural and soft tissue dysfunction in those with chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), and how these dysfunctions can be addressed to improve daily symptoms. Our working hypothesis is that diminished neurodynamics together with movement restrictions in associated soft tissues can contribute to the persistence of symptoms in a proportion of people with CFS. The causes of this neurodynamic dysfunction in general are not well understood, but acquired soft tissue and neural dysfunctions can result from cumulative physical trauma, inflammation, and other events in the course of normal life. In those at risk for CFS, these nerve and soft tissue dysfunctions could give rise to an increasingly sensitized nervous system during the time preceding the onset of symptoms. Our conceptual model proposes that CFS symptoms might arise or escalate once the patient exhausts his or her ability to compensate for pre-existing soft tissue and neurodynamic restrictions, such as might occur after a relatively brief period of inactivity following surgery or during an acute illness. Mechanical stretch of peripheral nerve tissues would then activate spinal dorsal horn neurons in a manner analogous to the painful input from acute injury, thereby contributing to central nervous system sensitivity. Central sensitivity in turn would be expected to heighten the sensitivity of peripheral nerves to further loading.

Patients with neural and soft tissue restrictions in the range observed in those with CFS typically experience worse symptoms after exercise. We speculate that this occurs as a consequence of the repetitive mechanical tension exerted on an already less than fully compliant nervous system. If so, the altered neurodynamics could be expected to interfere with the efficacy of otherwise appropriate exercise-based rehabilitation programs, and possibly with the success of symptom-based medical and psychiatric interventions. Conversely, if abnormal neurodynamics are a factor in the pathogenesis of symptoms, treating these abnormalities  would be expected to lead to improved responses to a range of interventions.

would be expected to lead to improved responses to a range of interventions.

Evaluation and treatment of areas of diminished soft tissue compliance and adverse neurodynamics by skilled manual practitioners in conjunction with comprehensive medical management has become an important part of our treatment approach to CFS. The goals of physical therapy treatment are to minimize the influences of these areas of movement restriction and to optimize normal physiologic movement and behaviors. Although the eventual functional goal of improved work tolerance is shared by both exercise-based and manual practitioners, manual practitioners first assess for and treat somatic dysfunctions that contribute to limited, symptomatic movement, before advancing the patient to progressively more strenuous activities. Restoration of mobility is essential for optimal strength and endurance training, and may not be included to any large extent in exercise-based programs.

Before beginning the assessment, and at the beginning and end of each treatment, it is helpful to obtain a 0-10 rating of the person’s symptoms, e.g., fatigue, cognitive fogginess, light-headedness, nausea, reflux, sweating and flushing, vision changes, headache, or any other symptoms. It is also helpful to know which are primary, and the sequence in which the symptoms are experienced. As testing is performed on a sensitive system, the person and the examiner can each have an immediate appreciation for the symptom generation and its corresponding test maneuver or position. Later, the application of treatment techniques can be more specific and can be guided by patient feedback and therefore, be less likely to create a crescendo of symptoms. Because of the heightened sensitivity of the nervous system and of the soft tissues in general in those with CFS, gentle handling of the parts to be tested and treated is the key  to successful outcomes. If parts are taken through too great an arc of movement, if improper positioning is utilized in the examination or treatment, or if the treatment techniques are direct or require too much resistance, symptoms are likely to be quickly elicited or exacerbated due to adverse tensioning. The duration of the testing and the extent to which the clinician works to reproduce symptoms will greatly affect the person’s symptoms, either those noted immediately or those with delayed onset. There is quite often a very fine line between getting the needed response and completely overdoing it, after which it is almost impossible to continue with testing or treating. Repeated provocational testing or the application of direct techniques that increase tissue tensions have cumulative effects. Tests and handling should be briefly applied, specific and performed only to the point of generating the sought after response. During treatment, use of direct methods, or those that impose a stretch or movement into tissue resistance, should generally be avoided, except in provocational tests to note initial and subsequent post-treatment status. These methods include direct whole muscle and myofascial stretching and direct joint and neuromobilization techniques. The preferred treatment approach utilizes an indirect method. In contrast to direct techniques, indirect techniques are gently applied in a direction opposite the barrier to movement, that is, to a position of greatest ease or balanced membranous tension. This method of treatment reduces the tension in the irritable tissues and minimizes the risk of further sensitizing them, promoting a more effective functional change. Examples of these indirect techniques include myofascial release in the direction of ease, functional technique, and strain and counter-strain. Induction and cranio-sacral techniques, very subtle techniques, can be either direct or indirect; a careful and specific application of these methods can provide excellent results.

to successful outcomes. If parts are taken through too great an arc of movement, if improper positioning is utilized in the examination or treatment, or if the treatment techniques are direct or require too much resistance, symptoms are likely to be quickly elicited or exacerbated due to adverse tensioning. The duration of the testing and the extent to which the clinician works to reproduce symptoms will greatly affect the person’s symptoms, either those noted immediately or those with delayed onset. There is quite often a very fine line between getting the needed response and completely overdoing it, after which it is almost impossible to continue with testing or treating. Repeated provocational testing or the application of direct techniques that increase tissue tensions have cumulative effects. Tests and handling should be briefly applied, specific and performed only to the point of generating the sought after response. During treatment, use of direct methods, or those that impose a stretch or movement into tissue resistance, should generally be avoided, except in provocational tests to note initial and subsequent post-treatment status. These methods include direct whole muscle and myofascial stretching and direct joint and neuromobilization techniques. The preferred treatment approach utilizes an indirect method. In contrast to direct techniques, indirect techniques are gently applied in a direction opposite the barrier to movement, that is, to a position of greatest ease or balanced membranous tension. This method of treatment reduces the tension in the irritable tissues and minimizes the risk of further sensitizing them, promoting a more effective functional change. Examples of these indirect techniques include myofascial release in the direction of ease, functional technique, and strain and counter-strain. Induction and cranio-sacral techniques, very subtle techniques, can be either direct or indirect; a careful and specific application of these methods can provide excellent results.

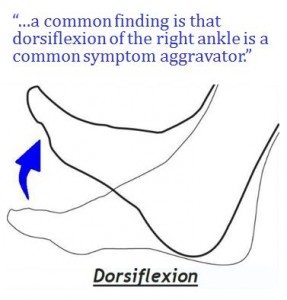

As movements and positions that provoke or heighten symptoms are discovered and treated, the person should be taught to recognize when he or she encounters these movements or postures in daily living and how to modify them so as to minimize their impact on symptom production. An example of a common finding is that dorsiflexion of the right ankle or flexion of the right hip past 70 degrees is a common symptom aggravator. As these findings are being treated manually, instruction can be given about modification of sitting posture so that feet are not tucked beneath chairs so as to prevent excessive dorsiflexion posturing and sustained soft tissue or neural loading. Following this same line of thinking, wearing shoes with a 1/2” to 3/4″ heel positions the ankle in a posture of reduced dorsiflexion and thus produces less strain during quiet standing or in roll-over when walking. Walking barefooted or in flip flops or flat sandals is discouraged. The hip flexion restriction is managed in the same fashion. The person might be instructed to sit on a stool or to sit in a chair or car seat with the seatback reclined to better accommodate the 70 degree available range of motion. This would prevent significant sustained soft tissue loading in 90 degrees or more of hip flexion that might otherwise insidiously increase symptoms. This is a problem frequently encountered in school or while studying at a desk. If not appreciated, these situations can unknowingly contribute to the persistent nature of fatigue and cognitive fogginess. Progressive return to repetitive and resistive activities is also essential in order to develop a gradual, but improving, tolerance for the demands of daily activity with the possibility of resuming classes at home or at school or performing job-related tasks. This goal can be attainable in those whose neural and soft tissue tensions begin to reduce, who modify daily or exercise activities, and who have good medical management. In clinical practice, the treatment method described above appears to improve tolerance of exercise and reduce the frequency and intensity of the many symptoms in CFS.

As movements and positions that provoke or heighten symptoms are discovered and treated, the person should be taught to recognize when he or she encounters these movements or postures in daily living and how to modify them so as to minimize their impact on symptom production. An example of a common finding is that dorsiflexion of the right ankle or flexion of the right hip past 70 degrees is a common symptom aggravator. As these findings are being treated manually, instruction can be given about modification of sitting posture so that feet are not tucked beneath chairs so as to prevent excessive dorsiflexion posturing and sustained soft tissue or neural loading. Following this same line of thinking, wearing shoes with a 1/2” to 3/4″ heel positions the ankle in a posture of reduced dorsiflexion and thus produces less strain during quiet standing or in roll-over when walking. Walking barefooted or in flip flops or flat sandals is discouraged. The hip flexion restriction is managed in the same fashion. The person might be instructed to sit on a stool or to sit in a chair or car seat with the seatback reclined to better accommodate the 70 degree available range of motion. This would prevent significant sustained soft tissue loading in 90 degrees or more of hip flexion that might otherwise insidiously increase symptoms. This is a problem frequently encountered in school or while studying at a desk. If not appreciated, these situations can unknowingly contribute to the persistent nature of fatigue and cognitive fogginess. Progressive return to repetitive and resistive activities is also essential in order to develop a gradual, but improving, tolerance for the demands of daily activity with the possibility of resuming classes at home or at school or performing job-related tasks. This goal can be attainable in those whose neural and soft tissue tensions begin to reduce, who modify daily or exercise activities, and who have good medical management. In clinical practice, the treatment method described above appears to improve tolerance of exercise and reduce the frequency and intensity of the many symptoms in CFS.

We are continuing our study of the role of soft tissue restriction, and that of nerve tissue in particular, to add greater diagnostic specificity to our approach. It is our expectation that a skilled manual approach to assessment will provide enhanced predictors for many of the components of CFS and that a manual approach to treatment will complement medical and surgical interventions and lead to more complete and lasting comfort and function.

Read Part 1 of this two-part article series.

Peter C. Rowe, M.D., is professor of pediatrics at Johns Hopkins Children’s Center where he directs the Chronic Fatigue Clinic. Kevin R. Fontaine, Ph.D., is a professor at University of Alabama at Birmingham; and Richard L. Violand, Jr., is a physical therapist in private practice at Violand and McNerney Physical Therapists, in Ellicott, MD. Dr. Rowe’s research project, “Neuromuscular Strain in CFS,” is being funded by the Solve ME/CFS Initiative under its Research Institute Without Walls. Dr. Rowe was part of a Johns Hopkins team that was the first to identify orthostatic intolerance as a key feature of CFS. He has cared for CFS patients in his medical practice and conducted research on CFS for nearly 20 years.